Fence Post Keeps Popping Up? Here’s How To Stop Frost Heaves

Back when I lived in the countryside, one of my neighbors pointed to a fence post on the low side of his property that stood 6 in. higher than the other posts. “I drove that post back down three years in a row,” he said, “but it still keeps popping up.” It wasn’t a persistent woodchuck at work. It was the annual work of winter-time frost.

Frost, the same light, delicate stuff that periodically coats your window glass in winter, is a surprisingly powerful natural force. It lifts the soil, cracks rocks and snaps trees, altering the landscape in almost every neighborhood that has freezing weather. Sidewalks crack and pop up like logjams; concrete driveways, front stoops, and steps rhythmically rise, fall or begin to creep away from houses or garages; and decks and patios begin to tilt. Fences lean to the side and retaining walls crack too.

Unfortunately, you won’t notice the effects of frost until the damage is done. Frost usually works slowly but steadily, year after year, lifting and shifting a wall or driveway until hairline cracks become gaping chasms. Or you’ll suddenly notice that the 1/4-in. gap between the house and porch has grown to a full inch, or the patio door won’t open because the concrete slab outside has risen and pushed up the sill.

In this article, you’ll learn how frost works, why it’s so powerful, and what you can do to limit its damage.

Why Frost Heave Occur

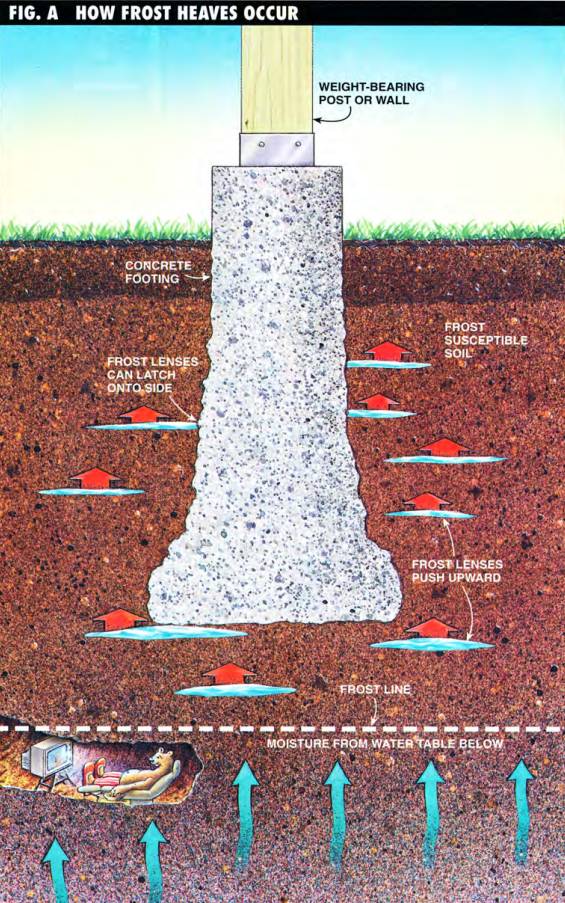

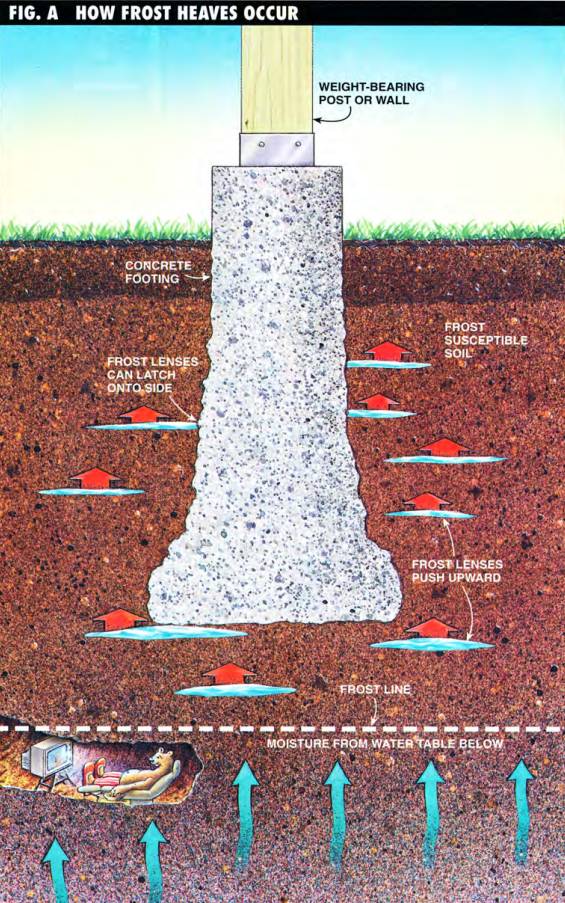

The frost that can lift and shift an entire building is no different than what forms on your window, but it’s more mysterious because it occurs underground. Fig. A gives you a gopher’s eye view of frost in action.

Frost pockets called “lenses” can form in the wet ground when it freezes. As a lens thickens, it thrusts the overlying soil or foundation upward. Frost can also latch onto the side of foundations and lift them.

When the outdoor temperature drops below 32 degrees F, the moisture in the ground begins to freeze, starting at the top. As you know, the upper level of soil gets rock hard, so that you need a pick to chip through the top layer if you have to dig a hole. Frost gradually works its way down as persistently cold weather cools the soil at ever deeper levels. If the soil is well-drained and contains little moisture, frost spreads evenly through the soil and won’t cause trouble. But if the soil is wet, the water will often freeze in a paper-thin sheet, called a lens.” Imagine a huge, thin contact lens buried underground.

Depending on the weather, these icy lenses can grow thicker, fed by water rising up through the soil from wetter soil below or from the water table. The water table is the level at which groundwater fully saturates the soil. It can begin anywhere from a few feet to more than 100 ft. under your house, depending on the climate and soil conditions in your locale.)

When water freezes, it expands about 9 percent in volume (which is why, of course, ice cubes float in your lemonade rather than clunking to the bottom). So when water freezes against the lens, it expands, thickens the lens and compresses the soil, eventually thrusting the soil upward along with everything on top of it. This uplift is called “frost heave.”

Usually, the heave is slow, creeping only a fraction of an inch over days. Yet the power of a frost heave is virtually unstoppable, because the expansive force of freezing water is huge, somewhere around 50,000 lbs. per sq. in. A frost heave can lift a seven-story building or collapse massive, steel-reinforced concrete walls. So foundations, garages, decks, patio slabs and just about everything else around your house won’t have much of a chance if a frost heave gets ahold of them.

When temperatures rise and the frost lens melts, the damage is already done. The cracks remain, and foundations, once heaved, never quite settle back to their original place. Each year they move a bit farther astray until you’ve got major problems.

Coping With Frost Heaves

People who live in the Southern Gulf States and on the Pacific Coast, where frost rarely penetrates the soil more than an inch or two, don’t need to worry about frost heaves. But the rest of us would live in topsy-turvy neighborhoods if builders didn’t design homes to prevent frost heaving in the first place.

Frost heaves commonly occur in two ways. Most often, a frost lens forms beneath a foundation or footing and heaves it upward. But ice crystals can also grab onto the rough or porous surface of a foundation or footing and lift it from the side (Fig. A).

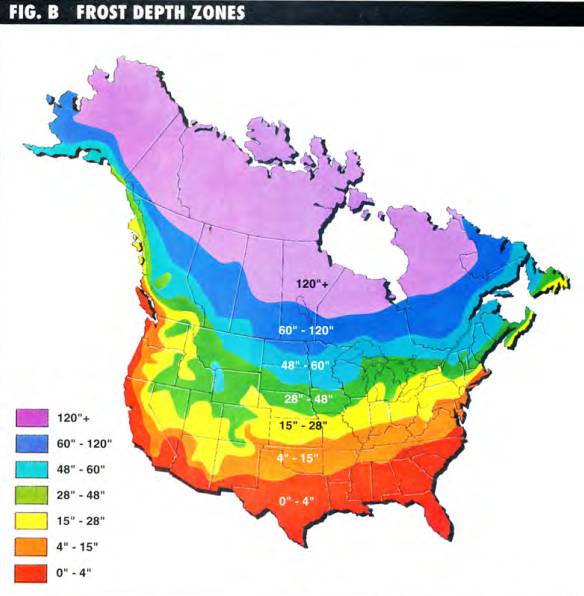

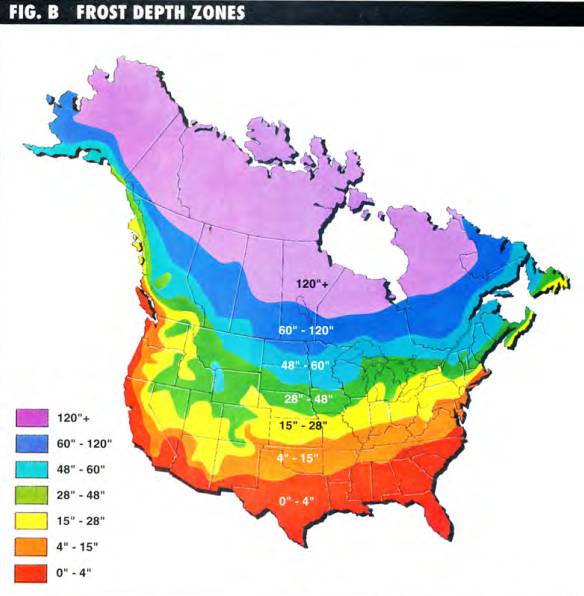

A shifting foundation will quickly ruin a home and cost the homeowner big bucks, so builders don’t take chances. When they build a house, they give it a “frost footing” made up of foundation walls or piers that extend below the “frost line” so a frost lens can’t form beneath it and lift the house. The frost line is the depth in the ground beyond which frost is not likely to penetrate (Fig. B).

The map shows approximate frost depths during a colder-than-average winter. The actual depth varies widely due to different soil types, the moisture content of the soil, and the ground cover (bare soil, turf, snow, etc.). The building code in your area specifies a frost line depth that all local building foundations must meet or exceed.

Your local building inspector will tell you the frost line depth for your area. It ranges from zero in much of California where little or no frost occurs, to 10 in. in parts of Kentucky, to 60 in. in frigid International Falls, MN.

Frost won’t usually latch onto the side of a house’s foundation because even a small amount of heat from the interior drives moisture in the soil away from the walls. However, frost sometimes grabs onto the foundation of an unheated structure.

Frost can work its mischief on porches, garages and decks too. If these “secondary” structures are connected to a house, building codes require that they have frost footings as well. That’s because these connected structures will damage the house if they heave. This may seem like a pain if you’re adding a deck or front porch, but porch floors can heave up under doors. and tilting decks can pull house walls outward. The cost of repairing a frost heave’s damage can easily exceed the original cost of a porch or deck.

Floating Structures

It’s usually not economical or necessary to put frost footings under secondary structures, including garages, decks, sidewalks, patios and retaining walls, if they’re not connected to the house. With proper precautions, these structures can safely “float” on top of the soil without frost footings.

But a mistake here can cause trouble — just ask my father-in-law. The concrete floor of his garage is steadily turning to rubble as it annually shifts, lifts and cracks (more on this later). You may encounter other common problems, such as concrete patio slabs that lift under door sills and jam the doors, and deck posts that shift and pull a deck away from the house.

To successfully prevent frost damage to floating structures, you have to take a close look at the soil you’re building on.

Frost And The Soil

Frost heaving doesn’t occur automatically whenever the weather turns cold. It requires a certain amount of moisture and a “frost-susceptible” soil. Soils that contain coarse particles of gravel and sand drain well and won’t usually heave, because they don’t collect and hold enough water to form frost lenses. They’re called “non-frost-susceptible” soils. Soils with finer particles like clays and silts, on the other hand, don’t drain as well and hold a lot of water. They’re called “frost-susceptible” soils.

Of course, most soils are mixtures of sands, clays, and silts, so you’re not likely to recognize any one type when you dig a footing hole for your deck. Unless you hit gravel or pure sand, it’s usually best to assume that your soil is somewhat frost susceptible.

But don’t despair. Even frost-susceptible soil usually won’t heave if you provide good drainage (assuming the water table is far enough underground). Good drainage would solve my father-in-law’s problem. His garage sits near the house in a slight depression that stays wet longer than other parts of the yard. Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to provide drainage now without major digging. Rather than scraping away the topsoil and putting the concrete slab on grade level, the garage builder should have dumped a foot or two of clean sand or gravel on top of the grade to build up the site. (Builders stipulate “clean” because even a 10 percent contamination by silts or clays can change the character of sand or gravel and make it frost susceptible.) This would have provided enough drainage and stability to keep the concrete slab intact.

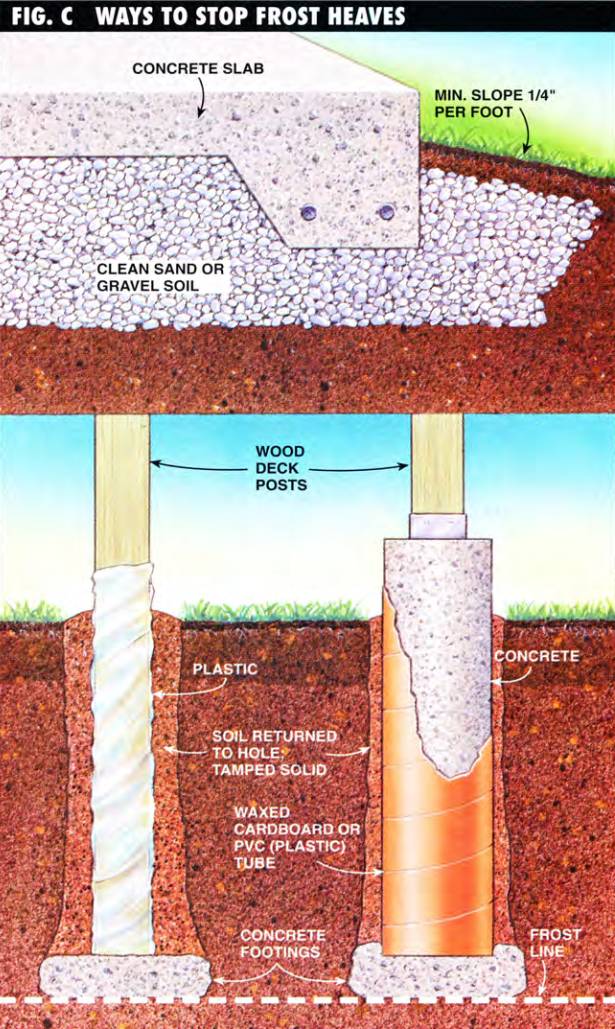

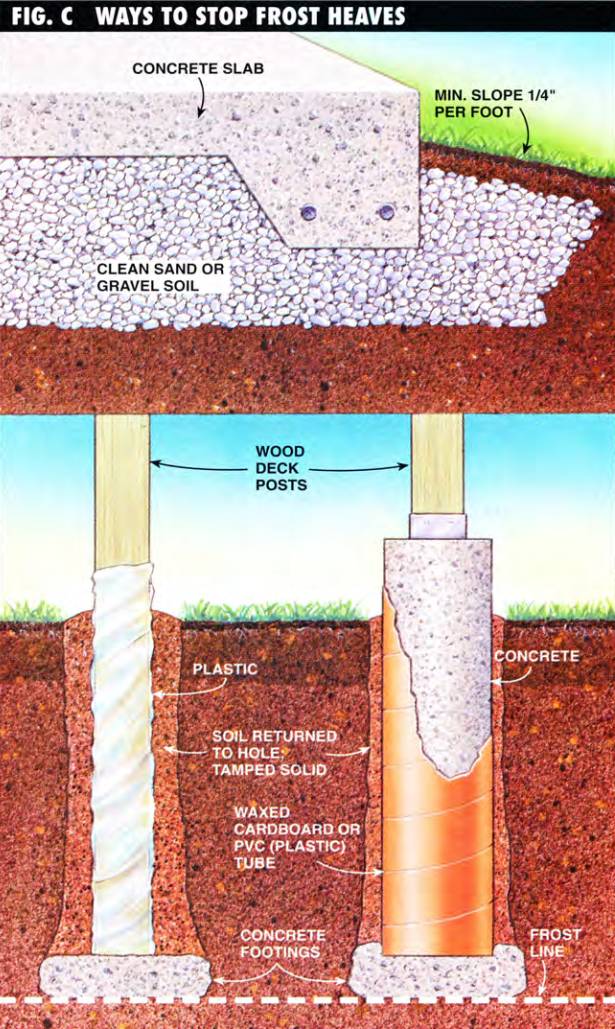

To prevent frost heaves, the easiest and least costly solution is to plan in advance for good drainage away from walks, patios, garages, decks and other floating structures (Fig. C).

A layer of clean sand or gravel under a concrete slab, combined with good drainage, will eliminate most frost heaves. The more frost-susceptible your soil, the thicker the bed of sand or gravel you’ll need. Piers wrapped in plastic, waxed tubes or PVC plastic pipe will resist frost heaving from the side.

And a bed of sand or gravel underneath improves drainage and decreases frost susceptibility.

Don’t hesitate to discuss soil conditions with your local building inspectors. They should be familiar with local conditions and able to warn you of potential trouble.

A Deck Builder's Problem

It’s not always feasible to provide good drainage in frost-susceptible soil for post footings for decks. Even if you put the footing down to the frost line, frost can still grab the side of the post or footing and push it up. In these cases it’s best to surround the post or concrete with a smooth surface of plastic, a waxed tube or plastic pipe (Fig. C) to keep frost from bonding to the sides and jacking up the footing. Refill the hole around the post or tube with the soil you dug out, making sure to tamp it down solidly in 6-in. increments as you fill the hole. Solidly packed soil, mounded at the top, will keep water from saturating the soil around the fooling and causing potential heaves. It’s tempting to fill the hole with sand or gravel, thinking you’ll provide good drainage that way. However, unless you also provide underground drainage, you’ll actually create a catch basin for water around the footing, making the potential for frost heaving even greater.

Back when I lived in the countryside, one of my neighbors pointed to a fence post on the low side of his property that stood 6 in. higher than the other posts. “I drove that post back down three years in a row,” he said, “but it still keeps popping up.” It wasn’t a persistent woodchuck at work. It was the annual work of winter-time frost.

Frost, the same light, delicate stuff that periodically coats your window glass in winter, is a surprisingly powerful natural force. It lifts the soil, cracks rocks and snaps trees, altering the landscape in almost every neighborhood that has freezing weather. Sidewalks crack and pop up like logjams; concrete driveways, front stoops, and steps rhythmically rise, fall or begin to creep away from houses or garages; and decks and patios begin to tilt. Fences lean to the side and retaining walls crack too.

Unfortunately, you won’t notice the effects of frost until the damage is done. Frost usually works slowly but steadily, year after year, lifting and shifting a wall or driveway until hairline cracks become gaping chasms. Or you’ll suddenly notice that the 1/4-in. gap between the house and porch has grown to a full inch, or the patio door won’t open because the concrete slab outside has risen and pushed up the sill.

In this article, you’ll learn how frost works, why it’s so powerful, and what you can do to limit its damage.

Why Frost Heave Occur

The frost that can lift and shift an entire building is no different than what forms on your window, but it’s more mysterious because it occurs underground. Fig. A gives you a gopher’s eye view of frost in action.

Frost pockets called “lenses” can form in the wet ground when it freezes. As a lens thickens, it thrusts the overlying soil or foundation upward. Frost can also latch onto the side of foundations and lift them.

When the outdoor temperature drops below 32 degrees F, the moisture in the ground begins to freeze, starting at the top. As you know, the upper level of soil gets rock hard, so that you need a pick to chip through the top layer if you have to dig a hole. Frost gradually works its way down as persistently cold weather cools the soil at ever deeper levels. If the soil is well-drained and contains little moisture, frost spreads evenly through the soil and won’t cause trouble. But if the soil is wet, the water will often freeze in a paper-thin sheet, called a lens.” Imagine a huge, thin contact lens buried underground.

Depending on the weather, these icy lenses can grow thicker, fed by water rising up through the soil from wetter soil below or from the water table. The water table is the level at which groundwater fully saturates the soil. It can begin anywhere from a few feet to more than 100 ft. under your house, depending on the climate and soil conditions in your locale.)

When water freezes, it expands about 9 percent in volume (which is why, of course, ice cubes float in your lemonade rather than clunking to the bottom). So when water freezes against the lens, it expands, thickens the lens and compresses the soil, eventually thrusting the soil upward along with everything on top of it. This uplift is called “frost heave.”

Usually, the heave is slow, creeping only a fraction of an inch over days. Yet the power of a frost heave is virtually unstoppable, because the expansive force of freezing water is huge, somewhere around 50,000 lbs. per sq. in. A frost heave can lift a seven-story building or collapse massive, steel-reinforced concrete walls. So foundations, garages, decks, patio slabs and just about everything else around your house won’t have much of a chance if a frost heave gets ahold of them.

When temperatures rise and the frost lens melts, the damage is already done. The cracks remain, and foundations, once heaved, never quite settle back to their original place. Each year they move a bit farther astray until you’ve got major problems.

Coping With Frost Heaves

People who live in the Southern Gulf States and on the Pacific Coast, where frost rarely penetrates the soil more than an inch or two, don’t need to worry about frost heaves. But the rest of us would live in topsy-turvy neighborhoods if builders didn’t design homes to prevent frost heaving in the first place.

Frost heaves commonly occur in two ways. Most often, a frost lens forms beneath a foundation or footing and heaves it upward. But ice crystals can also grab onto the rough or porous surface of a foundation or footing and lift it from the side (Fig. A).

A shifting foundation will quickly ruin a home and cost the homeowner big bucks, so builders don’t take chances. When they build a house, they give it a “frost footing” made up of foundation walls or piers that extend below the “frost line” so a frost lens can’t form beneath it and lift the house. The frost line is the depth in the ground beyond which frost is not likely to penetrate (Fig. B).

The map shows approximate frost depths during a colder-than-average winter. The actual depth varies widely due to different soil types, the moisture content of the soil, and the ground cover (bare soil, turf, snow, etc.). The building code in your area specifies a frost line depth that all local building foundations must meet or exceed.

Your local building inspector will tell you the frost line depth for your area. It ranges from zero in much of California where little or no frost occurs, to 10 in. in parts of Kentucky, to 60 in. in frigid International Falls, MN.

Frost won’t usually latch onto the side of a house’s foundation because even a small amount of heat from the interior drives moisture in the soil away from the walls. However, frost sometimes grabs onto the foundation of an unheated structure.

Frost can work its mischief on porches, garages and decks too. If these “secondary” structures are connected to a house, building codes require that they have frost footings as well. That’s because these connected structures will damage the house if they heave. This may seem like a pain if you’re adding a deck or front porch, but porch floors can heave up under doors. and tilting decks can pull house walls outward. The cost of repairing a frost heave’s damage can easily exceed the original cost of a porch or deck.

Floating Structures

It’s usually not economical or necessary to put frost footings under secondary structures, including garages, decks, sidewalks, patios and retaining walls, if they’re not connected to the house. With proper precautions, these structures can safely “float” on top of the soil without frost footings.

But a mistake here can cause trouble — just ask my father-in-law. The concrete floor of his garage is steadily turning to rubble as it annually shifts, lifts and cracks (more on this later). You may encounter other common problems, such as concrete patio slabs that lift under door sills and jam the doors, and deck posts that shift and pull a deck away from the house.

To successfully prevent frost damage to floating structures, you have to take a close look at the soil you’re building on.

Frost And The Soil

Frost heaving doesn’t occur automatically whenever the weather turns cold. It requires a certain amount of moisture and a “frost-susceptible” soil. Soils that contain coarse particles of gravel and sand drain well and won’t usually heave, because they don’t collect and hold enough water to form frost lenses. They’re called “non-frost-susceptible” soils. Soils with finer particles like clays and silts, on the other hand, don’t drain as well and hold a lot of water. They’re called “frost-susceptible” soils.

Of course, most soils are mixtures of sands, clays, and silts, so you’re not likely to recognize any one type when you dig a footing hole for your deck. Unless you hit gravel or pure sand, it’s usually best to assume that your soil is somewhat frost susceptible.

But don’t despair. Even frost-susceptible soil usually won’t heave if you provide good drainage (assuming the water table is far enough underground). Good drainage would solve my father-in-law’s problem. His garage sits near the house in a slight depression that stays wet longer than other parts of the yard. Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to provide drainage now without major digging. Rather than scraping away the topsoil and putting the concrete slab on grade level, the garage builder should have dumped a foot or two of clean sand or gravel on top of the grade to build up the site. (Builders stipulate “clean” because even a 10 percent contamination by silts or clays can change the character of sand or gravel and make it frost susceptible.) This would have provided enough drainage and stability to keep the concrete slab intact.

To prevent frost heaves, the easiest and least costly solution is to plan in advance for good drainage away from walks, patios, garages, decks and other floating structures (Fig. C).

A layer of clean sand or gravel under a concrete slab, combined with good drainage, will eliminate most frost heaves. The more frost-susceptible your soil, the thicker the bed of sand or gravel you’ll need. Piers wrapped in plastic, waxed tubes or PVC plastic pipe will resist frost heaving from the side.

And a bed of sand or gravel underneath improves drainage and decreases frost susceptibility.

Don’t hesitate to discuss soil conditions with your local building inspectors. They should be familiar with local conditions and able to warn you of potential trouble.

A Deck Builder's Problem

It’s not always feasible to provide good drainage in frost-susceptible soil for post footings for decks. Even if you put the footing down to the frost line, frost can still grab the side of the post or footing and push it up. In these cases it’s best to surround the post or concrete with a smooth surface of plastic, a waxed tube or plastic pipe (Fig. C) to keep frost from bonding to the sides and jacking up the footing. Refill the hole around the post or tube with the soil you dug out, making sure to tamp it down solidly in 6-in. increments as you fill the hole. Solidly packed soil, mounded at the top, will keep water from saturating the soil around the fooling and causing potential heaves. It’s tempting to fill the hole with sand or gravel, thinking you’ll provide good drainage that way. However, unless you also provide underground drainage, you’ll actually create a catch basin for water around the footing, making the potential for frost heaving even greater.