How To Build a Dry-Laid Patio – Costs, Pictures, and Detailed Instructions

How much does it cost to put in a patio?

My 550 sq. ft. patio cost me around $2,700 in materials and rental charges. I did all the work myself. My cost per square foot was $4.91. If I had hired someone to do it all, it’d cost me between $10 and $15 per square foot. Keep on reading to find out everything I learned in my patio project.

Build Your Own Dry-Laid Patio

A little ambition and a lot of muscle power will earn you this enduring dry-laid patio.

Whether it’s in the land of Oz or your own backyard, there’s something magical about a brick path — especially if it leads to a sunny, spacious patio.

Don’t get me wrong; there’s nothing magical about how patios get built. They take loads of energy and muscle power. They require careful planning from the first shovelful of dirt thrown to the last paver laid. But you’ll get what you work for: a beautiful, usable, outdoor space that will last a lifetime.

This patio is “dry-laid,” meaning there’s no wet concrete used, just precast concrete pavers laid on a bed of sand. Ours is a large ambitious project with curves, paths, and steps. We circled trees, looped around landscaping beds and linked together two decks.

Every patio is different — the one you build may be larger, smaller, squarer or rounder. The good news is, everything you need to know about building any dry-laid patio is right here on this article.

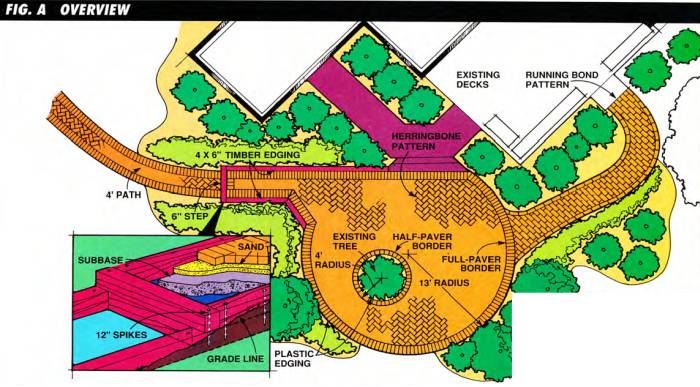

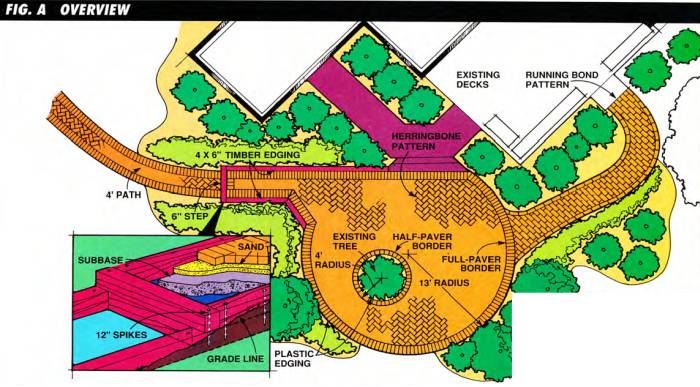

Fig. A: Overview

Pavers: Beautiful, Versatile, Manageable

One of the beauties of pavers is that together they create a large, durable space, but individually they’re light-weight and easy to install. This gives DIYers the permanence of concrete without the special tools, know-how and “hurry-upness” that concrete requires. Plus, pavers have color, shape, and pizzazz.

There’s no doubt about the durability of concrete pavers. They’re often used in streets and industrial parking lots where heavy machinery cracks ordinary concrete slabs.

Pavers — small and independent — withstand abuse by flexing, rather than cracking, under pressure. They’re ideal for regions that go through freeze/thaw cycles, too; the individual pavers absorb heaving and movement without cracking. And it’s a lot easier to repair small areas in a dry-laid patio than with a slab.

The simple rectangular pavers used here can be laid in a variety of patterns (Fig. B). Other paver shapes are available: squares, zigzags, keyholes, even some that look like fancy floor tile. Shop around at home improvement and landscaping centers.

Fig. B: Paver Patterns

Pavers can be used for driveways, sidewalks, patios, garden paths, even porch floors.

As long as the underlying gravel and sand base is properly prepared, pavers can be used almost anywhere. In areas where vehicles will travel, the subbase (Fig. C) must be increased to at least 10 in.

Fig. C: Timber edging and step detail.

The Best Design For You And Your Yard

Whether you’re a novice or experienced DIYer, you’ll find this project doable and satisfying. You’ll be limited more by your energy level and tree time than by the skills required.

A well-designed patio must take into account the terrain, landscape, and the needs and pocketbook of your family. Not all yards are candidates for a patio. In uneven terrain, a raised deck – which can span hill and dale – might be the best option for outdoor space.

This patio needed to be tied with existing trees, planting beds, and decks. Everything was measured and a small scale drawing of the home and existing landscape was made on paper (Fig. A).

We used a straight, 16-ft. 2x4 with a 4-ft. level on it and a tape measure to get a rough idea of how much the yard sloped (that was noted on the drawing, too).

Then all was needed was to lay tracing paper on top of the scale drawing and doodle a half-dozen patio designs. A consultation with a landscape designer provided the following helpful tips:

- Patios must have a slight slope (1 in. for every 4 to 8 ft.) for proper drainage. If you don’t provide enough slope, rainwater will settle into low spots, eventually softening and washing out the sand and subbase materials beneath. A flat or poorly sloped patio could even direct water into your basement. Too much slope and you’ll feel you’re on a listing ship. Bear in mind you can build up low spots with an extra-thick layer of subbase.

- Ask yourself how you’ll be using your patio. My expert recommended a minimum of 25 sq. ft. of patio per house occupant. He also added that a patio at least 16 ft. long in one direction is often the most functional. Plan for at least a 6x6-ft. area out of any traffic path for a dining table and chairs. Do you need space for a grill? Lounge chairs? A wading pool? Planters? Hopscotch? Sketch these on your tracing paper as you doodle.

- In small areas, use simple pavers and patterns (like the running bond shown in Fig. B). In large areas, you can break up the expanse with a variety of patterns or dividing bands.

- Curves add interest and grace to the patio — but also loads of cutting and extra work.

Pavers, Materials, And Tools

I paid 80¢ each (a little over $3 per sq. ft.) for my 4 x 8-in. pavers. I purchased them from a landscape center, where they supplied me with brochures from the paver manufacturer and gave me lots of installation tips.

When ordering pavers, estimate the square footage of your patio, then add 5%. If you have a lot of curves, borders or half pavers — like this patio — order 10% extra. This allows for damaged pavers and provides extra ones for future repairs. The plastic edging cost $4.50 per ft; the 12-in. spikes to secure it cost 70¢ each.

I used “class 5” crushed limestone for building the subbase. Class 5, a grade of material commonly used for road beds, is widely available. It consists of 3/4-in. rock and smaller particles, which nest together firmly when compacted. When ordering, tell the quarry or trucking company you’ll be using the material for a patio subbase. If they don’t have class 5 limestone they should be able to offer crushed gravel or another suitable substitute.

The class 5 used here cost around $140 (7 cubic yards at $10 per yard plus a $70 delivery charge). One cubic yard of class 5, when placed 4 in. deep will cover 81 sq. ft. If you need to build up an area, order more.

Coarse sand for leveling and bedding the pavers ran $25 a cubic yard, plus delivery. One yard of sand will provide a 1-in. base for about 300 sq. ft. of patio. Order a little extra for sweeping into the cracks when you finish – my patio consumed about four 5-gal. buckets of sand for this.

For tools, you’ll use everyday hammers, levels and tape measures, as well as big, oddball tools like a flat-plate vibrator and a masonry saw that you’ll need to rent ($70 to $80 each per day). With proper planning. you shouldn’t need to rent either tool for more than two whole or half days.

All the materials and rental charges for this project came to $2,700. That’s a lot! But when you consider the pros charge between $10 and $15 per sq. ft. when they supply and install pavers, you’ll see you’re saving 1/2 to 2/3 the cost by doing it yourself.

Planning And Layout

The first thing you should think about is where the last paver you lay will wind up. Will your yard accommodate the slope and size of your patio? Will a square patio end in nice, full pavers or skinny little slivers?

With your graph paper plan in hand, lay down garden hose (Photo 1) and 2x4s to form an outline of your patio. Use your level and a straight 2x4 to double-check the lay of the land for proper slope.

Outline the patio perimeter using a garden hose for curved areas and long 2x4s for straight sections.

Then spray-paint a line 8 in. outside the outline of your patio to act as a line for excavating. Strip away the sod at this point (Photo 2), so grass doesn’t get in the way of the guide strings you’ll soon be setting up.

Remove sod in an area extending 8 in. beyond the boundaries of the patio. Spray paint indicates the excavation line.

Excavating The Site And Building The Base

This part of the project is the key to a successful (and long-lasting) patio.

Use the bottom of a door or a set of stairs abutting the patio area as the starting point for establishing the final height and slope of your patio. Your entire slab should slope away from the house at a rate of 1 in. every 4 to 8 in.

This slope may be one long decline or a slight dome-shape so water runs off in more than one direction.

Place one end of a long 2x4 at the bottom of the stairway or an inch below the door threshold, then level across to stakes driven at the perimeter of the patio and make a mark (Photo 3).

Make another mark the appropriate distance down the stake to indicate the slope. In this case, after making a level mark on our stake with a level and 12ft. 2x4, another mark was made 2 in. down to indicate a slope of 2 in. for that 12 ft. (1 in. for every 6 ft).

Use a level, a 2x4, and stakes to determine the slope of the patio. A slope of 1 in. per 4 to 8 ft. away from your house is the ideal. Run stakes and a grid of string to mark the top of the finished patio, then excavate 7-1/2 in. below strings.

Make a gridwork of stakes and guide strings to indicate the finished height and slope of your patio, then excavate 7-1/2 in below these lines. This will provide room for a 4-in. subbase, the 1-in. sand base, and the 2-1/2 in. pavers themselves (4 + 1 + 2-1/2 = 7-1/2 in.). See Fig. C.

If the area is hilly, you’ll need to go back and forth between excavating, leveling, and setting strings to get things right.

Soil conditions vary greatly across the country. If after digging 7-1/2 in. below your strings, you still find pockets of loose dirt or black soil, remove it or it will eventually settle, creating a wavy patio.

Next, bring in the subbase material. Bring the area up to a height of 3-1/2 in. below your guide strings (Photo 4). It should be at least 4 in deep in all places The subbase should extend 8 in. beyond the actual edge of the patio to provide room for the edging.

Spread Class 5 subbase to a depth of 4 in. over the entire patio area and 8 in. beyond. Measure down from the guide strings to establish a uniform height at subbase.

It’s possible you’ll need to build up an area to accommodate your patio. In such cases, remove the sod and loose soil, then build up the area with your subbase material. Building a 10- to 12-in. subbase is common; even 20 in. would not be unusual.

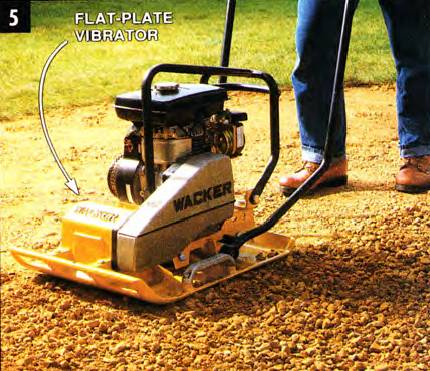

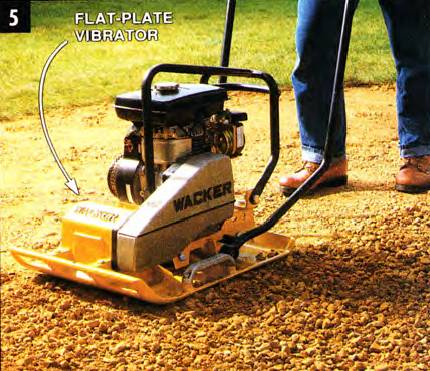

Compact the class 5 using a flat-plate vibrator (also known as a compactor) as shown in Photo 5. Go over the entire area twice.

Tamp the subbase using a flat-plate vibrator (rented at $65 a day). Work in a circular motion and compact the area twice.

The Essential Edging

Edging is an absolute must for maintaining the integrity of your patio. Without solid edging, your sand base and pavers will separate and drift apart as rain, frost and foot traffic pound away.

I used plastic edging. Left uncut, it remains straight and rigid, but when it’s cut it can be bent to form curves. Secure the edging into the compacted subbase with 12-in. spikes (Photo 6).

Install the edging on the tamped subbase using 12-in. spikes. Cut the webbing on the edging’s backside to make it flex for curves.

I used landscape timbers for combination edging/steps in a sloped area of the yard (Photo 7). Crisscross corners and use double timbers on the front of steps (even though the lower one will be buried).

Install landscape timbers for edging in areas where you need to change levels or step down. Be certain to overlap corners.

This lower timber prevents the subbase and sand from washing out. The tops of the timbers should be at the same height as the surface of the finished patio.

Spreading Sand

Sand provides the final base for your pavers. If this surface is uneven, the pavers on top will be, too.

Ideally, the sand should be 1 in. thick, but if it’s a tad thicker or thinner in spots, that’s okay. What you want is a firm, flat surface for laying pavers.

Sand also locks the pavers in place. When you vibrate the pavers, they’ll bed themselves slightly into the sand.

If your patio is under 10 ft. wide, use a screed board with a 2-in. notch on the ends to ride along the edging to level the sand (similar to that in the first photo below).

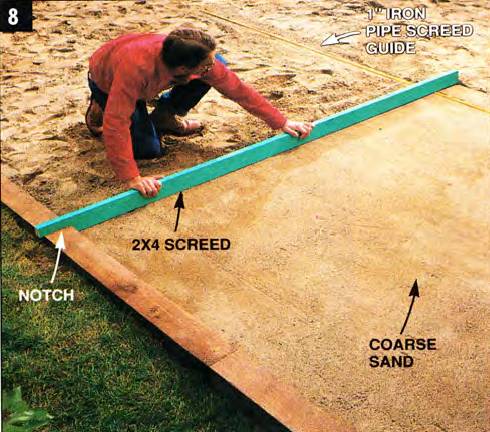

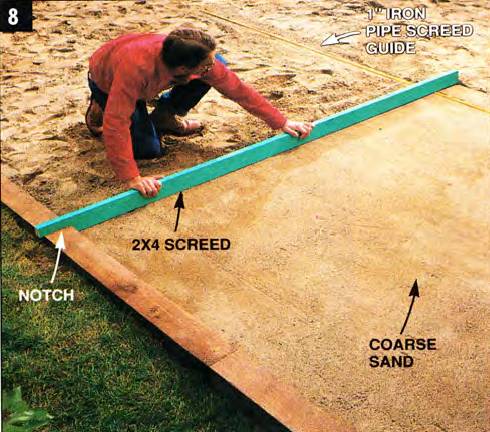

On larger expanses, level long lengths of iron pipe in the sand 2 in. below your guide strings, then run your screed along the top of the pipes. (When you’re done with the pipe, remove it, then fill in the groove it leaves with sand). In many cases, you’ll use a combination — a notched screed board riding along the edging on one end, with the other end of the screed running along the iron pipe (Photo 8).

Spread ad level a 1-in. bed of sand over compacted subbase. Pipes provide a guide for dragging the 2x4 screed board across.

Whichever screeding method you use, roughly dump and level the sand over the compacted subbase, then fill in low spaces and rake away the excess sand as you drag your 2x4. Shuffle the screed lightly from side to side as you work. You’re not compacting the sand, just creating a firm, solid bed.

Screed only as much sand as you can cover with pavers in one day. Screeded sand left any longer is guaranteed to be ruffled by wind, rain, kids or a stray cat thinking he’s found the world’s biggest litter box.

Pave Away

Install the pavers starting along the longest, straightest edge. Border pavers provide a crisp finished edge, especially along curved portions of the patio.

You should now be standing before an expanse of sand that’s flat as a pancake (but slightly sloped). Take down the guide strings you used to determine height and slope and put up new stakes and strings to mark the lines for the pattern of your pavers (Photo 10).

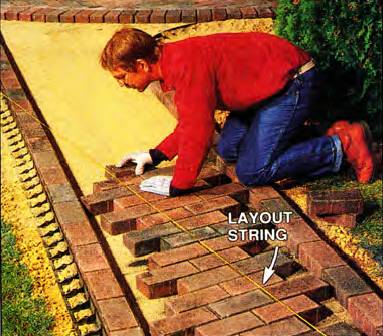

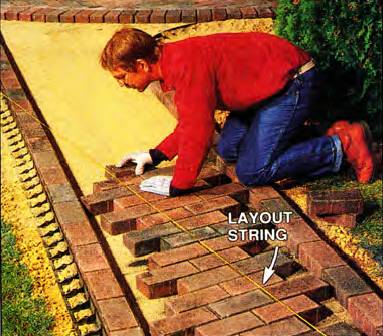

Continue laying pavers using a layout string to keep them in line as you work. Put a gap between pawn or lap them tighter to stay in line.

Stay along with your house or other long straight edge and lay down the border pavers. A border isn’t essential, but adds a crisp, finished look, especially along curves.

Then lay the rest of your pavers in your selected pattern Just lay the pavers in place — don’t bang on them or twist them.

Measure over to your string every few rows to make sure you’re staying on track. You can leave a slight gap between pavers or tap them tighter together with a rubber mallet.

If you’ve taken the time to set things up right, laying the pavers goes amazingly fast. Many pavers have little nubs on the sides to serve as spacers. Don’t walk or kneel on the edge of the patio until after you’ve vibrated it; otherwise, these pavers can sink unevenly.

The pavers here were let run “wild” near the curved edges (Photo 11).

Mark pavers that run “wild” into the border area. Then remove the paver, cut to size, and place back in position along with border paver.

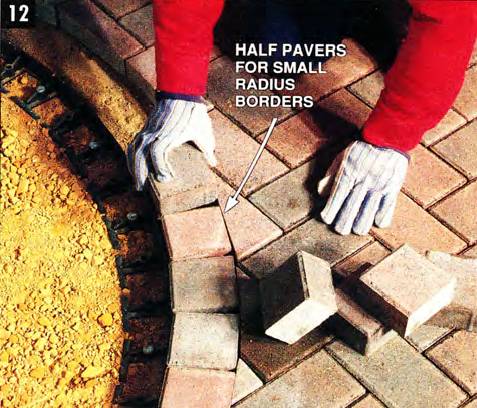

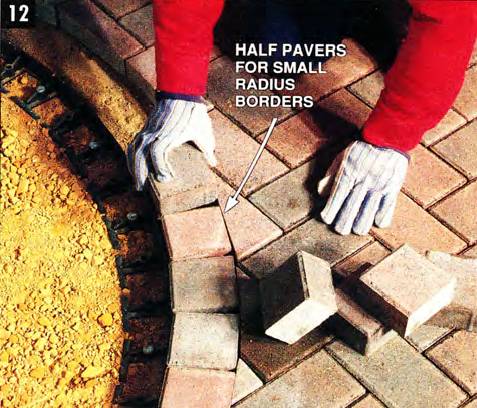

Using a paver as a guide, I marked the inner pavers, removed and cut them on a masonry saw, then reinstalled the cut inner and the border pieces. On tight radius circles, we used half payers for the border (Photo 12) to avoid large, pie-shaped voids between them.

Use half pavers for bordering tight circles. Smaller pavers cut down on the size of the pie-shaped gaps between each piece.

As big and foreign as the masonry cutting saw appears, it’s actually safe and easy to use. A constant stream of recirculating water keeps the blade cool and lubricated, and a sliding tray carries the paver past the blade. A cut takes about 10 seconds. Remember to wear your eye and hearing protection.

Cut pavers on a masonry saw. This saw has a built-in sliding carriage for moving pavers past the blade. The recirculating water keeps the blade cool and lubricated.

When all your pavers are cut and in place, vibrate the entire patio (Photo 14), starting at the outer edge and working inward in a circular motion.

The vibrator will lock the pavers into the sand and help even up the surface. Don’t let the vibrator sit in one place too long, or pavers could settle unevenly or crack. Some pros place plywood down and vibrate on top of that to help distribute the weight of the machine.

Tamp the patio with a flat-plate vibrator after all the pavers an installed. Tamp the entire outside edge first, then circle in.

If a paver sinks deeper than its neighbors, use a pair of screwdrivers to pry it up, sprinkle a little extra sand in the void, then replace the paver.

Sweeping And Upkeep

Spread coarse sand across the surface of your patio. After the sand dries, sweep it around the patio (Photo 15) to fill the spaces between the payers.

Sweep coarse, dry sand between cracks of pavers to lock them together and fill voids. Repeat with more dry sand in a few days.

Make sure the sand is dry — wet sand will bridge, rather than fill the gaps. It may take two sweepings with a push broom a few days apart to completely fill the gaps.

The sand helps solidify the pavers, and also fills any spaces where dirt might enter to provide a mini-planting bed for weeds.

Two coats of a water sealer were rolled over the completed patio. This wasn’t done to protect the pavers — they don’t need protecting! The purpose was to enrich the color.

Landscape around your patio with grass, sod or planting beds to give it a finished look. Bring in the dirt to even out the space between the new patio and existing yard. Keep dirt at least 1/2 in. below any plastic edging to allow rainwater and runoff to easily drain away from the patio.

Set up your Adirondack chair and take a snooze – you’ve earned it!

Landscape around the completed patio with flowers, shrubs, and grass. Grass will loot through the open spaces in flexible edging to anchor it in place.

Pathways

A pathway can be part of a larger project or a project in itself. A walkway made of pavers is an attractive way to link your driveway to your front door, existing deck to the new patio, or back door to garden area.

Here are a few tips:

- Keep the pattern simple; a border running parallel to the path with a simple staggered pattern within is often the most attractive.

- Put a slight tilt in the path for drainage. One-half inch across a 3-ft. wide path is adequate.

- Take extra care to keep the edgings an equal distance apart; it will make screeding, cutting and paver laying easier.

Smooth and level the sand using a notched screed board riding along the edging for a guide. Include a slight tilt for good drainage.

Install the border, marking and cutting every other paver at an angle at curved areas.

Lay the pavers using a string for a guideline. Cut and Install pieces that butt up to the border later.

Shoveling Smarts

This project scores a 9.9 in sweat equity.

You’ll be amazed at the amount of dirt you remove, even with the smallest patio. Compacted earth, once dug up and tossed, tends to double its previous size.

Move it as few times as possible — preferably once.

If you’re going to use the dirt to fill in a low area, shovel the sod and dirt right into the wheelbarrow and dump it in its final resting spot.

If it’s going to be hauled away, back the trailer, truck or trash bin as close as you can.

Be equally wise with the materials you haul in.

Do all your excavating, then have your subbase dumped directly on the patio site.

Have your leveling sand and pavers delivered close to the patio. This patio took 2,500 pavers — that’s a lot of hauling by hand!

Consider access to your backyard:

- Can you back a truck close to the patio site?

- If not, are you prepared to do a lot of hauling by wheelbarrow?

- Will that heavy truck damage any tree roots or your soft asphalt driveway on a hot day?

- Have you carefully figured the amount of materials you need before ordering, so you don’t wind up with tons of extra sand, subbase or pavers?

- Does it make sense to temporarily remove a section of fence for access during the project?

Finally, consider recruiting help for some of the more labor-intensive parts: excavating, spreading the subbase, lugging the pavers.

How much does it cost to put in a patio?

My 550 sq. ft. patio cost me around $2,700 in materials and rental charges. I did all the work myself. My cost per square foot was $4.91. If I had hired someone to do it all, it’d cost me between $10 and $15 per square foot. Keep on reading to find out everything I learned in my patio project.

Build Your Own Dry-Laid Patio

A little ambition and a lot of muscle power will earn you this enduring dry-laid patio.

Whether it’s in the land of Oz or your own backyard, there’s something magical about a brick path — especially if it leads to a sunny, spacious patio.

Don’t get me wrong; there’s nothing magical about how patios get built. They take loads of energy and muscle power. They require careful planning from the first shovelful of dirt thrown to the last paver laid. But you’ll get what you work for: a beautiful, usable, outdoor space that will last a lifetime.

This patio is “dry-laid,” meaning there’s no wet concrete used, just precast concrete pavers laid on a bed of sand. Ours is a large ambitious project with curves, paths, and steps. We circled trees, looped around landscaping beds and linked together two decks.

Every patio is different — the one you build may be larger, smaller, squarer or rounder. The good news is, everything you need to know about building any dry-laid patio is right here on this article.

Fig. A: Overview

Pavers: Beautiful, Versatile, Manageable

One of the beauties of pavers is that together they create a large, durable space, but individually they’re light-weight and easy to install. This gives DIYers the permanence of concrete without the special tools, know-how and “hurry-upness” that concrete requires. Plus, pavers have color, shape, and pizzazz.

There’s no doubt about the durability of concrete pavers. They’re often used in streets and industrial parking lots where heavy machinery cracks ordinary concrete slabs.

Pavers — small and independent — withstand abuse by flexing, rather than cracking, under pressure. They’re ideal for regions that go through freeze/thaw cycles, too; the individual pavers absorb heaving and movement without cracking. And it’s a lot easier to repair small areas in a dry-laid patio than with a slab.

The simple rectangular pavers used here can be laid in a variety of patterns (Fig. B). Other paver shapes are available: squares, zigzags, keyholes, even some that look like fancy floor tile. Shop around at home improvement and landscaping centers.

Fig. B: Paver Patterns

Pavers can be used for driveways, sidewalks, patios, garden paths, even porch floors.

As long as the underlying gravel and sand base is properly prepared, pavers can be used almost anywhere. In areas where vehicles will travel, the subbase (Fig. C) must be increased to at least 10 in.

Fig. C: Timber edging and step detail.

The Best Design For You And Your Yard

Whether you’re a novice or experienced DIYer, you’ll find this project doable and satisfying. You’ll be limited more by your energy level and tree time than by the skills required.

A well-designed patio must take into account the terrain, landscape, and the needs and pocketbook of your family. Not all yards are candidates for a patio. In uneven terrain, a raised deck – which can span hill and dale – might be the best option for outdoor space.

This patio needed to be tied with existing trees, planting beds, and decks. Everything was measured and a small scale drawing of the home and existing landscape was made on paper (Fig. A).

We used a straight, 16-ft. 2x4 with a 4-ft. level on it and a tape measure to get a rough idea of how much the yard sloped (that was noted on the drawing, too).

Then all was needed was to lay tracing paper on top of the scale drawing and doodle a half-dozen patio designs. A consultation with a landscape designer provided the following helpful tips:

- Patios must have a slight slope (1 in. for every 4 to 8 ft.) for proper drainage. If you don’t provide enough slope, rainwater will settle into low spots, eventually softening and washing out the sand and subbase materials beneath. A flat or poorly sloped patio could even direct water into your basement. Too much slope and you’ll feel you’re on a listing ship. Bear in mind you can build up low spots with an extra-thick layer of subbase.

- Ask yourself how you’ll be using your patio. My expert recommended a minimum of 25 sq. ft. of patio per house occupant. He also added that a patio at least 16 ft. long in one direction is often the most functional. Plan for at least a 6x6-ft. area out of any traffic path for a dining table and chairs. Do you need space for a grill? Lounge chairs? A wading pool? Planters? Hopscotch? Sketch these on your tracing paper as you doodle.

- In small areas, use simple pavers and patterns (like the running bond shown in Fig. B). In large areas, you can break up the expanse with a variety of patterns or dividing bands.

- Curves add interest and grace to the patio — but also loads of cutting and extra work.

Pavers, Materials, And Tools

I paid 80¢ each (a little over $3 per sq. ft.) for my 4 x 8-in. pavers. I purchased them from a landscape center, where they supplied me with brochures from the paver manufacturer and gave me lots of installation tips.

When ordering pavers, estimate the square footage of your patio, then add 5%. If you have a lot of curves, borders or half pavers — like this patio — order 10% extra. This allows for damaged pavers and provides extra ones for future repairs. The plastic edging cost $4.50 per ft; the 12-in. spikes to secure it cost 70¢ each.

I used “class 5” crushed limestone for building the subbase. Class 5, a grade of material commonly used for road beds, is widely available. It consists of 3/4-in. rock and smaller particles, which nest together firmly when compacted. When ordering, tell the quarry or trucking company you’ll be using the material for a patio subbase. If they don’t have class 5 limestone they should be able to offer crushed gravel or another suitable substitute.

The class 5 used here cost around $140 (7 cubic yards at $10 per yard plus a $70 delivery charge). One cubic yard of class 5, when placed 4 in. deep will cover 81 sq. ft. If you need to build up an area, order more.

Coarse sand for leveling and bedding the pavers ran $25 a cubic yard, plus delivery. One yard of sand will provide a 1-in. base for about 300 sq. ft. of patio. Order a little extra for sweeping into the cracks when you finish – my patio consumed about four 5-gal. buckets of sand for this.

For tools, you’ll use everyday hammers, levels and tape measures, as well as big, oddball tools like a flat-plate vibrator and a masonry saw that you’ll need to rent ($70 to $80 each per day). With proper planning. you shouldn’t need to rent either tool for more than two whole or half days.

All the materials and rental charges for this project came to $2,700. That’s a lot! But when you consider the pros charge between $10 and $15 per sq. ft. when they supply and install pavers, you’ll see you’re saving 1/2 to 2/3 the cost by doing it yourself.

Planning And Layout

The first thing you should think about is where the last paver you lay will wind up. Will your yard accommodate the slope and size of your patio? Will a square patio end in nice, full pavers or skinny little slivers?

With your graph paper plan in hand, lay down garden hose (Photo 1) and 2x4s to form an outline of your patio. Use your level and a straight 2x4 to double-check the lay of the land for proper slope.

Outline the patio perimeter using a garden hose for curved areas and long 2x4s for straight sections.

Then spray-paint a line 8 in. outside the outline of your patio to act as a line for excavating. Strip away the sod at this point (Photo 2), so grass doesn’t get in the way of the guide strings you’ll soon be setting up.

Remove sod in an area extending 8 in. beyond the boundaries of the patio. Spray paint indicates the excavation line.

Excavating The Site And Building The Base

This part of the project is the key to a successful (and long-lasting) patio.

Use the bottom of a door or a set of stairs abutting the patio area as the starting point for establishing the final height and slope of your patio. Your entire slab should slope away from the house at a rate of 1 in. every 4 to 8 in.

This slope may be one long decline or a slight dome-shape so water runs off in more than one direction.

Place one end of a long 2x4 at the bottom of the stairway or an inch below the door threshold, then level across to stakes driven at the perimeter of the patio and make a mark (Photo 3).

Make another mark the appropriate distance down the stake to indicate the slope. In this case, after making a level mark on our stake with a level and 12ft. 2x4, another mark was made 2 in. down to indicate a slope of 2 in. for that 12 ft. (1 in. for every 6 ft).

Use a level, a 2x4, and stakes to determine the slope of the patio. A slope of 1 in. per 4 to 8 ft. away from your house is the ideal. Run stakes and a grid of string to mark the top of the finished patio, then excavate 7-1/2 in. below strings.

Make a gridwork of stakes and guide strings to indicate the finished height and slope of your patio, then excavate 7-1/2 in below these lines. This will provide room for a 4-in. subbase, the 1-in. sand base, and the 2-1/2 in. pavers themselves (4 + 1 + 2-1/2 = 7-1/2 in.). See Fig. C.

If the area is hilly, you’ll need to go back and forth between excavating, leveling, and setting strings to get things right.

Soil conditions vary greatly across the country. If after digging 7-1/2 in. below your strings, you still find pockets of loose dirt or black soil, remove it or it will eventually settle, creating a wavy patio.

Next, bring in the subbase material. Bring the area up to a height of 3-1/2 in. below your guide strings (Photo 4). It should be at least 4 in deep in all places The subbase should extend 8 in. beyond the actual edge of the patio to provide room for the edging.

Spread Class 5 subbase to a depth of 4 in. over the entire patio area and 8 in. beyond. Measure down from the guide strings to establish a uniform height at subbase.

It’s possible you’ll need to build up an area to accommodate your patio. In such cases, remove the sod and loose soil, then build up the area with your subbase material. Building a 10- to 12-in. subbase is common; even 20 in. would not be unusual.

Compact the class 5 using a flat-plate vibrator (also known as a compactor) as shown in Photo 5. Go over the entire area twice.

Tamp the subbase using a flat-plate vibrator (rented at $65 a day). Work in a circular motion and compact the area twice.

The Essential Edging

Edging is an absolute must for maintaining the integrity of your patio. Without solid edging, your sand base and pavers will separate and drift apart as rain, frost and foot traffic pound away.

I used plastic edging. Left uncut, it remains straight and rigid, but when it’s cut it can be bent to form curves. Secure the edging into the compacted subbase with 12-in. spikes (Photo 6).

Install the edging on the tamped subbase using 12-in. spikes. Cut the webbing on the edging’s backside to make it flex for curves.

I used landscape timbers for combination edging/steps in a sloped area of the yard (Photo 7). Crisscross corners and use double timbers on the front of steps (even though the lower one will be buried).

Install landscape timbers for edging in areas where you need to change levels or step down. Be certain to overlap corners.

This lower timber prevents the subbase and sand from washing out. The tops of the timbers should be at the same height as the surface of the finished patio.

Spreading Sand

Sand provides the final base for your pavers. If this surface is uneven, the pavers on top will be, too.

Ideally, the sand should be 1 in. thick, but if it’s a tad thicker or thinner in spots, that’s okay. What you want is a firm, flat surface for laying pavers.

Sand also locks the pavers in place. When you vibrate the pavers, they’ll bed themselves slightly into the sand.

If your patio is under 10 ft. wide, use a screed board with a 2-in. notch on the ends to ride along the edging to level the sand (similar to that in the first photo below).

On larger expanses, level long lengths of iron pipe in the sand 2 in. below your guide strings, then run your screed along the top of the pipes. (When you’re done with the pipe, remove it, then fill in the groove it leaves with sand). In many cases, you’ll use a combination — a notched screed board riding along the edging on one end, with the other end of the screed running along the iron pipe (Photo 8).

Spread ad level a 1-in. bed of sand over compacted subbase. Pipes provide a guide for dragging the 2x4 screed board across.

Whichever screeding method you use, roughly dump and level the sand over the compacted subbase, then fill in low spaces and rake away the excess sand as you drag your 2x4. Shuffle the screed lightly from side to side as you work. You’re not compacting the sand, just creating a firm, solid bed.

Screed only as much sand as you can cover with pavers in one day. Screeded sand left any longer is guaranteed to be ruffled by wind, rain, kids or a stray cat thinking he’s found the world’s biggest litter box.

Pave Away

Install the pavers starting along the longest, straightest edge. Border pavers provide a crisp finished edge, especially along curved portions of the patio.

You should now be standing before an expanse of sand that’s flat as a pancake (but slightly sloped). Take down the guide strings you used to determine height and slope and put up new stakes and strings to mark the lines for the pattern of your pavers (Photo 10).

Continue laying pavers using a layout string to keep them in line as you work. Put a gap between pawn or lap them tighter to stay in line.

Stay along with your house or other long straight edge and lay down the border pavers. A border isn’t essential, but adds a crisp, finished look, especially along curves.

Then lay the rest of your pavers in your selected pattern Just lay the pavers in place — don’t bang on them or twist them.

Measure over to your string every few rows to make sure you’re staying on track. You can leave a slight gap between pavers or tap them tighter together with a rubber mallet.

If you’ve taken the time to set things up right, laying the pavers goes amazingly fast. Many pavers have little nubs on the sides to serve as spacers. Don’t walk or kneel on the edge of the patio until after you’ve vibrated it; otherwise, these pavers can sink unevenly.

The pavers here were let run “wild” near the curved edges (Photo 11).

Mark pavers that run “wild” into the border area. Then remove the paver, cut to size, and place back in position along with border paver.

Using a paver as a guide, I marked the inner pavers, removed and cut them on a masonry saw, then reinstalled the cut inner and the border pieces. On tight radius circles, we used half payers for the border (Photo 12) to avoid large, pie-shaped voids between them.

Use half pavers for bordering tight circles. Smaller pavers cut down on the size of the pie-shaped gaps between each piece.

As big and foreign as the masonry cutting saw appears, it’s actually safe and easy to use. A constant stream of recirculating water keeps the blade cool and lubricated, and a sliding tray carries the paver past the blade. A cut takes about 10 seconds. Remember to wear your eye and hearing protection.

Cut pavers on a masonry saw. This saw has a built-in sliding carriage for moving pavers past the blade. The recirculating water keeps the blade cool and lubricated.

When all your pavers are cut and in place, vibrate the entire patio (Photo 14), starting at the outer edge and working inward in a circular motion.

The vibrator will lock the pavers into the sand and help even up the surface. Don’t let the vibrator sit in one place too long, or pavers could settle unevenly or crack. Some pros place plywood down and vibrate on top of that to help distribute the weight of the machine.

Tamp the patio with a flat-plate vibrator after all the pavers an installed. Tamp the entire outside edge first, then circle in.

If a paver sinks deeper than its neighbors, use a pair of screwdrivers to pry it up, sprinkle a little extra sand in the void, then replace the paver.

Sweeping And Upkeep

Spread coarse sand across the surface of your patio. After the sand dries, sweep it around the patio (Photo 15) to fill the spaces between the payers.

Sweep coarse, dry sand between cracks of pavers to lock them together and fill voids. Repeat with more dry sand in a few days.

Make sure the sand is dry — wet sand will bridge, rather than fill the gaps. It may take two sweepings with a push broom a few days apart to completely fill the gaps.

The sand helps solidify the pavers, and also fills any spaces where dirt might enter to provide a mini-planting bed for weeds.

Two coats of a water sealer were rolled over the completed patio. This wasn’t done to protect the pavers — they don’t need protecting! The purpose was to enrich the color.

Landscape around your patio with grass, sod or planting beds to give it a finished look. Bring in the dirt to even out the space between the new patio and existing yard. Keep dirt at least 1/2 in. below any plastic edging to allow rainwater and runoff to easily drain away from the patio.

Set up your Adirondack chair and take a snooze – you’ve earned it!

Landscape around the completed patio with flowers, shrubs, and grass. Grass will loot through the open spaces in flexible edging to anchor it in place.

Pathways

A pathway can be part of a larger project or a project in itself. A walkway made of pavers is an attractive way to link your driveway to your front door, existing deck to the new patio, or back door to garden area.

Here are a few tips:

- Keep the pattern simple; a border running parallel to the path with a simple staggered pattern within is often the most attractive.

- Put a slight tilt in the path for drainage. One-half inch across a 3-ft. wide path is adequate.

- Take extra care to keep the edgings an equal distance apart; it will make screeding, cutting and paver laying easier.

Smooth and level the sand using a notched screed board riding along the edging for a guide. Include a slight tilt for good drainage.

Install the border, marking and cutting every other paver at an angle at curved areas.

Lay the pavers using a string for a guideline. Cut and Install pieces that butt up to the border later.

Shoveling Smarts

This project scores a 9.9 in sweat equity.

You’ll be amazed at the amount of dirt you remove, even with the smallest patio. Compacted earth, once dug up and tossed, tends to double its previous size.

Move it as few times as possible — preferably once.

If you’re going to use the dirt to fill in a low area, shovel the sod and dirt right into the wheelbarrow and dump it in its final resting spot.

If it’s going to be hauled away, back the trailer, truck or trash bin as close as you can.

Be equally wise with the materials you haul in.

Do all your excavating, then have your subbase dumped directly on the patio site.

Have your leveling sand and pavers delivered close to the patio. This patio took 2,500 pavers — that’s a lot of hauling by hand!

Consider access to your backyard:

- Can you back a truck close to the patio site?

- If not, are you prepared to do a lot of hauling by wheelbarrow?

- Will that heavy truck damage any tree roots or your soft asphalt driveway on a hot day?

- Have you carefully figured the amount of materials you need before ordering, so you don’t wind up with tons of extra sand, subbase or pavers?

- Does it make sense to temporarily remove a section of fence for access during the project?

Finally, consider recruiting help for some of the more labor-intensive parts: excavating, spreading the subbase, lugging the pavers.